Long Term Impacts

The long-term impacts following the decision of Wong Kim Ark v United States including government policy expansion. For example, it acted as precedent for Native Americans and other minority groups pushing for citizenship rights. The U.S. Department of State has used the case to uphold the 14th amendment and guarantee citizenship to all born in the United States, demonstrating how Wong Kim Ark was the frontier for U.S. birthright citizenship.

The Lasting Effects of Wong Kim Ark

The 14th Amendment and Wong Kim Ark’s case were specifically referenced by the U.S. Department of State. They declared that all children born in the U.S., regardless of parental citizenship status, have the right to birthright citizenship.

“All children born in and subject, at the time of birth, to the jurisdiction of the United States: acquire U.S. citizenship at birth even if their parents were in the United States illegally at the time of birth.

(1) The U.S. Supreme Court examined at length the theories and legal precedents on which the U.S. citizenship laws are based in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898)... The Court affirmed that a child born in the United States to Chinese parents acquired U.S. citizenship.”

~ (7 FAM 1111 (d)(1))

Wong Kim Ark: The Contest Over Birthright Citizenship (2005) suggests that despite the efforts to overturn Wong Kim Ark, it has become a widely accepted and well established rule that will not be taken down with ease.

“The birthright citizenship doctrine of Wong Kim Ark has remained intact for over a century, still perceived by most to be a natural and well-established rule in accordance with American principles and practice. It is unlikely to be uprooted easily.”

~ Salyer, Lucy E. (2005). "Wong Kim Ark: The Contest Over Birthright Citizenship". In Martin, David; Schuck, Peter (eds.). Immigration Stories. New York: Foundation Press.

Asian migration, 19th and Early 20th Century

Connie Yu’s story, a grandmother separated from American born children, 1941

The Indian Citizenship Act (1924)

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all non citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.”

~ See House Report No. 222, Certificates of Citizenship to Indians, 68th Congress, 1st Session, Feb. 22, 1924

The Indian Citizenship Act (1924) expanded the foundational rights illustrated in Wong Kim Ark’s case to a greater population, in this case being Native Americans. This act nullified the ruling of the Elk v. Wilkins precedent.

Coolidge with Native Americans, White House, January 1924, Library of Congress

Wheeler-Howard Act, signing of the first tribal constitution

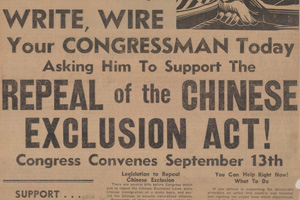

Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act (1946)

The ruling in Wong Kim Ark’s case reaffirmed that the 14th amendment would apply to all, regardless of ethnicity. To say Wong Kim Ark was not a citizen would invalidate the citizenship of children from European immigrant parents.

“To hold that the fourteenth amendment of the constitution excludes from citizenship the children born in the United States of citizens or subjects of other countries . . . would be to deny citizenship to thousands of persons of English, Scotch, Irish, German, or other European parentage, who have always been considered and treated as citizens of the United States.” Accordingly, the Court held that Wong Kim Ark had acquired citizenship at birth despite his parents’ alienage and despite the bar on their naturalization.”

~ Congressional Research Service

The Wong Kim Ark court decision led to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1946, which opened the United States to Chinese immigration as well as offered current U.S. immigrants a pathway to citizenship through naturalization- countering the harmful effects from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

“In 1943, Congress passed a measure to repeal the discriminatory exclusion laws against Chinese immigrants and to establish an immigration quota for China of around 105 visas per year. As such, the Chinese were both the first to be excluded in the beginning of the era of immigration restriction and the first Asians to gain entry to the United States in the era of liberalization.”

~ Department of State, Nat Office of the Historian

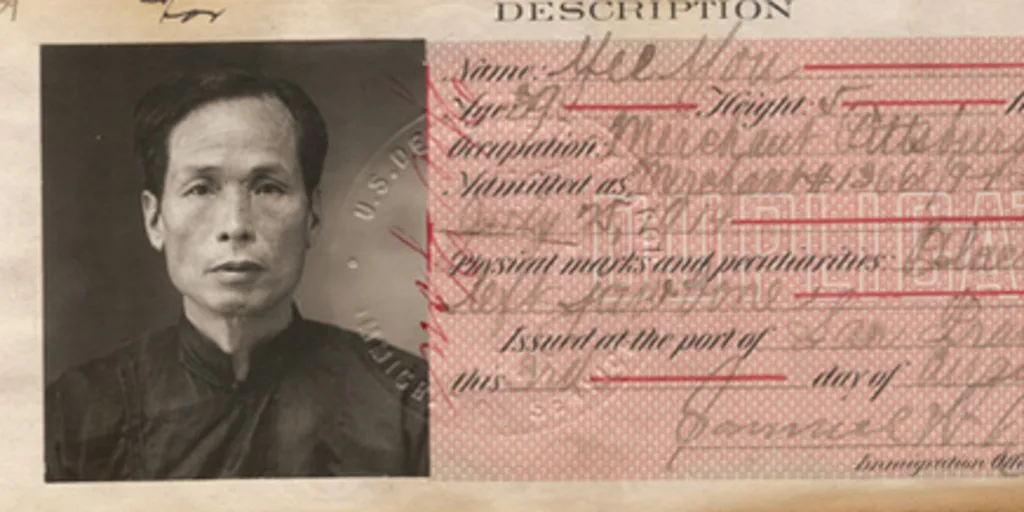

U.S. immigrant identity cards before the exclusion law, 1914, S.F. National Archives

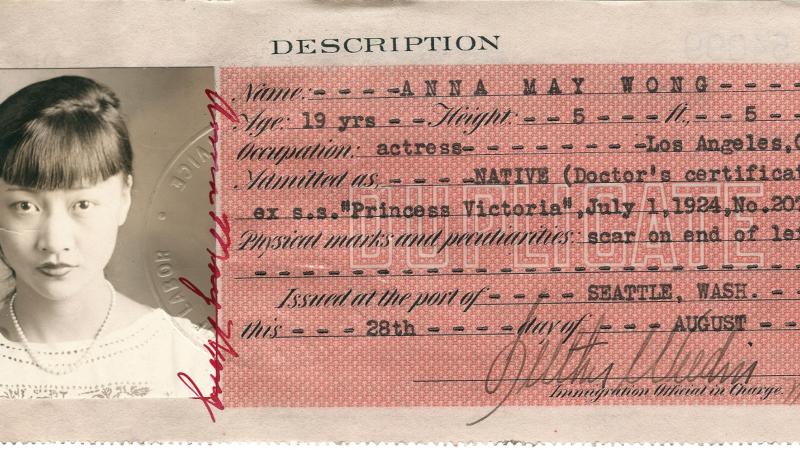

Anna May Wong Certificate of Identity, August 28, 1924, S.F. National Archives

“Write Your Congressman,” Chinese Press, September 10, 1943